How does a piano player intertpret a slur?

From a pianist’s point of view, a slur is a marking that tells you to play legato. But that’s only the beginning. To dig into the details, let’s start with the smallest slurs, and work our way up to the largest ones.

The Two-Note Slur Is a Thing of Its Own

The two-note slur is different than all the other slurs in that its meaning is precise, while its interpretations are limited. In other words, there’s a lot that you should do, and you have some – but not much – choice about it.

When the first note of a two-note slur occupies a more-important metric position, it is always accented.

What is a “metric position,” and what makes one of them more important than another? A note’s metric position is the exact location of the note within the measure, as measured against the time signature: for instance, the downbeat, the second beat, the “and” of two, etc. There are simple rules that govern the importance of these positions:

- The downbeat of any measure is the most important position in that measure.

- If the measure can be divided equally in two without having to subdivide the beat, then the half-way-through point is the second most important position in the measure. If the measure cannot be equally divided in two, all beats other than the downbeat are equal to one another (and less important than the downbeat).

- Beats are more important than their subdivisions.

- Primary subdivisions are more important than secondary subdivisions. For instance, when a quarter note is subdivided into sixteenths, the third sixteenth note (which occupies the same position as the eighth note) is more important than the second or fourth sixteenths. (Note that the second and fourth sixteenths are equal to one another.) This same hierarchy applies to all further subdivisions (32nds, 64ths).

What do I mean by “importance?”

Sometimes, “importance” means that a note in an important position should receive an accent. For instance, you may have heard common time described as four beats, with a primary accent on the first and a secondary accent on the third. This is true enough, but if it were taken as the whole truth, it would in fact be horribly misleading. If you were to examine recordings by your favorite pianists with this idea in mind, you’d certainly find that these seasoned and well informed musicians do not religiously place accents on such notes. Sometimes they do, and sometimes they don’t. Nor, I would add, do I believe composers would expect them to. That’s why I prefer the word “importance” to “accent.” Important things happen in important locations. Sometimes, that means accent. Often, however, it means that important compositional elements, such as harmonic rhythm, dissonance, resolution, phrase climaxes, rhythmic patterns, accompanimental patterns, etc. are going to be laid into the metrical framework with a very precise correlation to the relative importance of the beats. Depending on how this is done, emphasizing important beats by giving them accents may be desirable, or not.

When I use the word “accent” in this context, I’m referring specifically to metric accents, which are distinct from accent markings (articulations).

In general, accent markings in piano music are percussive events. Metric accents are generally better described as points of emphasis. English language provides a perfect example. Metric accents are similar to the emphasis we give to certain syllables within multisyllabic words. Normally, these accents are subtle and the listener gives them no attention whatsoever … unless something goes wrong. Mispronounce a word, and suddenly this aspect of speech becomes glaringly obvious. Do everything right, and normally, no one will be conscious of this aspect of your speech. Do it with nuance, and people will think you’re smart and marvelous.

It’s important to note that sometimes, metric accents do rise to the level of percussive events, and in fact, English language provides an excellent parallel. Normally, the stress in the word “undo” is subtle, but consider the sentence, “I know how do to it, but how do I undo it???” In certain situations, performers might raise the level of metric accent in a similar manner.

We can now return to our discussion of two-note slurs. As I was saying, when the first note falls on a more-important metric position, it is always emphasized. Subtly, overtly – it’s a matter of taste and context. As a pianist, I match the first note of a two-note slur with a downward stroke of my arm, the dropped weight of my arm, a deliberate downward stroke with my finger, etc. I modify these techniques to produce more or less emphasis according to context.

The second note of a two-note slur counterbalances the first.

The second note of the two note slur, I match with an upward motion, or I play it without arm weight, or with a finger-staccato, etc. My aim here is to de-emphasize the note, make it softer, shorter perhaps, less important. There’s a point of interpretation here: if the music is excited or upbeat, or if the two-note slur occurs within a context of staccato notes, I will make the second note of the two-note slur staccato. If the music is of a more serious or somber nature, I will deliberately float off the note, rather than cut it off abruptly. Regardless of the articulation, I will endeavor to make the second note sound less important than the first.

Sometimes, the second note of a two-note slur falls on a more-important metric position.

This is comparatively much less common. When it occurs, you must obey the same rule of placing the emphasis on the metrically more important of the two, which reverses the two-note slur’s accent pattern.

It’s important to note that although I feel this is a mainstream, modern position, not all musicians feel this way, or have felt this way throughout keyboard history. Of note, Mozart’s father – who was an important pedagogue – thought that all two note slurs should be played in the manner in which I initially described them, regardless of their metric position. Others of his colleagues agreed with him.

The More-Than-Two-Notes Slur

Once a slur covers more than two notes, it become simpler. If any of the notes occupies a more important metric position than the others – which is almost always the case – you should consider emphasizing it. Whether or not you’ll choose to depends on a great many things that are outside the scope of this topic. Instead, in terms of “what a slur is,” in this context, it simply means to play legato.

The Phrase Marking

Once a slur encompasses enough notes, it might be considered to be a phrase marking. It still carries the literal meaning of “play legato,” but new considerations arise.

When does a slur become a phrase?

There is no easy answer. In a textbook case, a slur becomes a phrase when it lasts for four measure and the music that coincides with its ending forms a cadence. Neither of these elements, though, can be considered a rule. Many phrases are shorter or longer than four measures, even though four measures is considered standard. In some cases, composers will avoid obvious cadences in order to create a sense of unrest or forward motion even among phrases. The best answer, in this case, is also the most subjective: a phrase is complete musical thought. It’s similar to what a sentence (or a clause) is in English.

Once you’ve determined that a particular slur does indeed indicate a phrase, you must do two things:

You must shape the phrase.

In the simplest sense, this means you should choose a single note that represents the climax of the phrase. You should crescendo toward and diminuendo away from this climax. In the most obvious case, this note would fall on an important metric position and would also be the highest note in the phrase.

Many phrases aren’t so simple. They may have primary and secondary (or more) climaxes. In such a scenario, you’d have to create a complex phrase shape that’s more like a mountain range than a single mountain.

The climax of a phrase may not be obvious. Sometimes there will be no one, single high note. In that case, the one that occupies the stronger metric position would likely be the winner. Sometimes there might be a singular high note, but it might occupy a weak metric position. In that case, a strong metric position close to that high note might the place to look to create your climax – or you might even decide to emphasize a small group of notes that encompasses both the weak-position high note and the one on the strongest position nearest to it.

Some pianists – to great effect – create a “negative climax” by playing the climactic note softer rather than louder. Even so, the principle is the same in that the climax is singled out for emphasis.

Although a phrase that climaxes on a high note is the most common type, a phrase might climax on a low note. Notes in the middle of the phrase’s pitch range are less common. There’s room for interpretation when it comes to pitch. But with meter, not so much. Phrases climaxing on notes that occupy unimportant metric positions are indeed rare, and would out of necessity be supported with explicit articulations and/or dynamic indications.

You cannot leave out intuition and creativity in considering the shapes of phrases. Sometimes, what you most need is imagination, and to hell with the rules.

You must breathe. Usually.

In piano music, and in the context of phrasing, “breathing” means to lift your hand at the end of a slur and detach that note from the one that follows, creating an actual – although slight – audible silence. This goes hand in hand with dynamic phrase shaping, and it would be fair to say that it is these things together – the detachment and the shaping, often in addition to a sense of timing (rubato) – that create breath. However, as with so many aspects of music, what I’ve described is a model that not all music follows.

Style and Pedal

The “breathing” model described above is most often followed when the music is of an obvious vocal nature: melodic, lyrical. However, in certain styles of piano music in which the pedal plays a heavy role, the pedal will very often obscure the breath to the degree that it prevents an audible silence. Nonetheless, the music will breathe in every other way.

Organization

A slur inevitably means to play legato. That is unescapable. However, sometimes a slur’s purpose is more one of organization than articulation. Sometimes, what a composers is showing you with a slur isn’t musical sentences, but musical words. When that is the case, breathing in between words may or may not make sense. It depends on your sense of style and your understanding of the composer’s style. In music that is not explicitly vocal in nature, it may be difficult to distinguish between this kind of organizational slur and a phrasing slur. One has to examine the underlying structure of the music to identify melodic and harmonic cadences and goals and determine how legato and non-legato articulation might assist in illuminating it.

Absence of Slurs, and Non-Legato or Multi-Slur Phrasing

It’s worth pointing out that the absence of a slur doesn’t necessarily indicate non-legato playing. It depends on context. When slurs are generally not present in a score, most pianists default to legato playing. Composers know this, and rely on it. It’s only when slurs are carefully and thoroughly marked that their absence indicates non-legato playing. Furthermore, it is not uncommon – especially in the Alberti accompaniments of music from the Classical Period – for the LH to be mostly devoid of slurs, where it’s clear that fully non-legato playing isn’t desirable or even possible. Pianists vary in their approach to such playing. Some play the LH legato. Others play with a brilliant sound that is legato in the sense that one doesn’t perceive explicit detachment, but isn’t legato in that a lyrical sense of connection isn’t present, nor is any overlapping of the notes. It’s light, bright, clean, and somewhat mechanical. Still, there are other pianists who do in fact play non-legato Alberti accompaniments when the tempo allows for it.

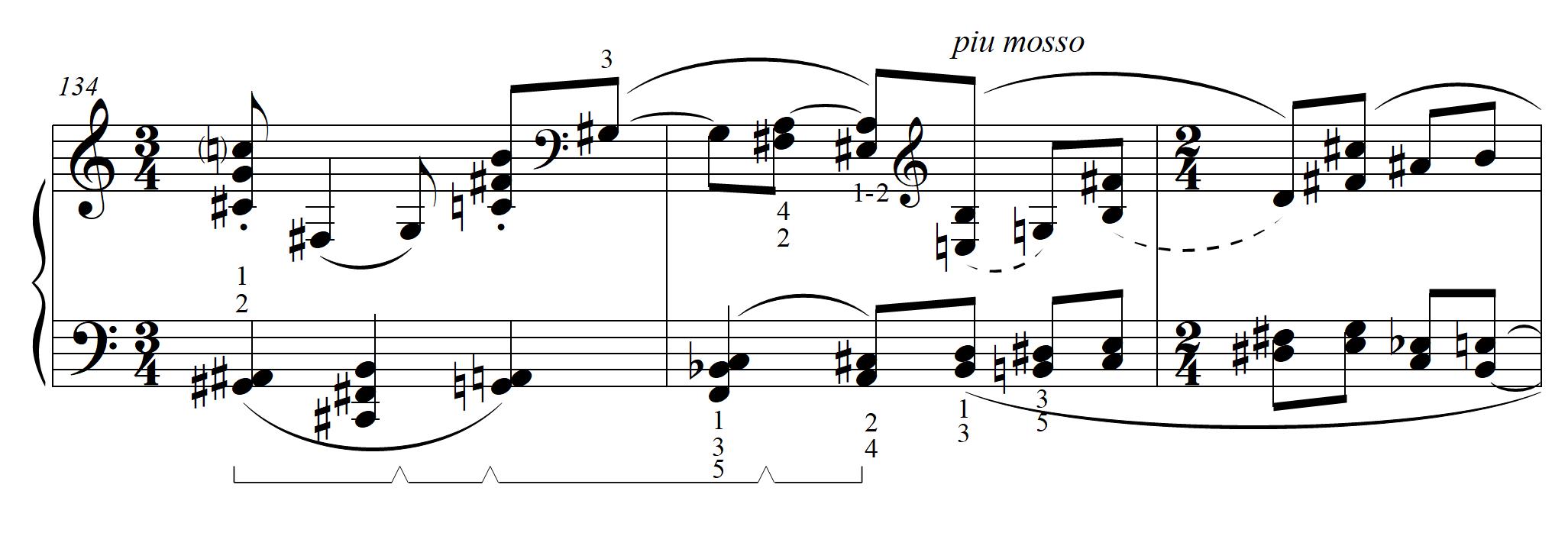

In music with long and/or complex phrases – in Romantic music, for instance – a composer may wish to use slurs to indicate the phrase’s components, rather than the full phrase. These components may be “words,” or they may be longer that “words,” but shorter than full phrases … akin to using commas and dashes within longer sentences, which makes sentence structure easier to perceive. Some composers leave it at that, and the player has to figure out where the full phrases are. Other composers use multiple slurs, some over the shorter units, and one large one over the phrase itself. A device available to modern composers is the dashed slur, which is used to show cohesive units such as phrases, while not implying legato. This can be useful if one wants to tie a bunch of component slurs together, but it can also be used – in the absence of slurs – to indicate a phrase where legato playing isn’t intended at all.

Repeated Notes under a Slur

If you were to look at all the repeated notes in the piano repertoire, most of them don’t have slurs over them. Can a pianist play legato repeated notes? Yes and no. Pianists play legato either by overlapping notes – even if that overlap is micro-thin – or by placing the attack of one note so close to the release of the note before it that there is no “space” (or audible silence) between them whatsoever. The former technique isn’t possible to execute on repeated notes. The latter technique is: it’s possible to release a note and re-strike it so quickly that there is no audible silence in between them. However, no matter how carefully this technique is executed, the result sounds like a “portamento” style of legato at best. Still, it’s worth doing.

Or course, the use of the pedal can eliminate any silence between repeated notes, and could be used to create a beautiful legato. The musical context of the repeated notes may or may not allow for this kind of pedaling; often, it doesn’t.

Still, one way or another, repeated notes under a slur should not have audible silences between them (unless you believe the composer or editor was careless in marking the slur).

Very well written and helpful. Many thanks!

Wow, thank John!

Very helpful. Can you suggest any reference on the same topic for further reading? Thanks.

Good Lord, no! I mean, I’ve read on it quite a bit, but I’d have to really search through my notes to find the references. But I will look, and I’ll post the info when I come across it.

GREAT ARTICLE! Exactly answered my question. Thank you!

You’re welcome!