Chopin Nocturne, Op. 9, No. 2: not a waltz

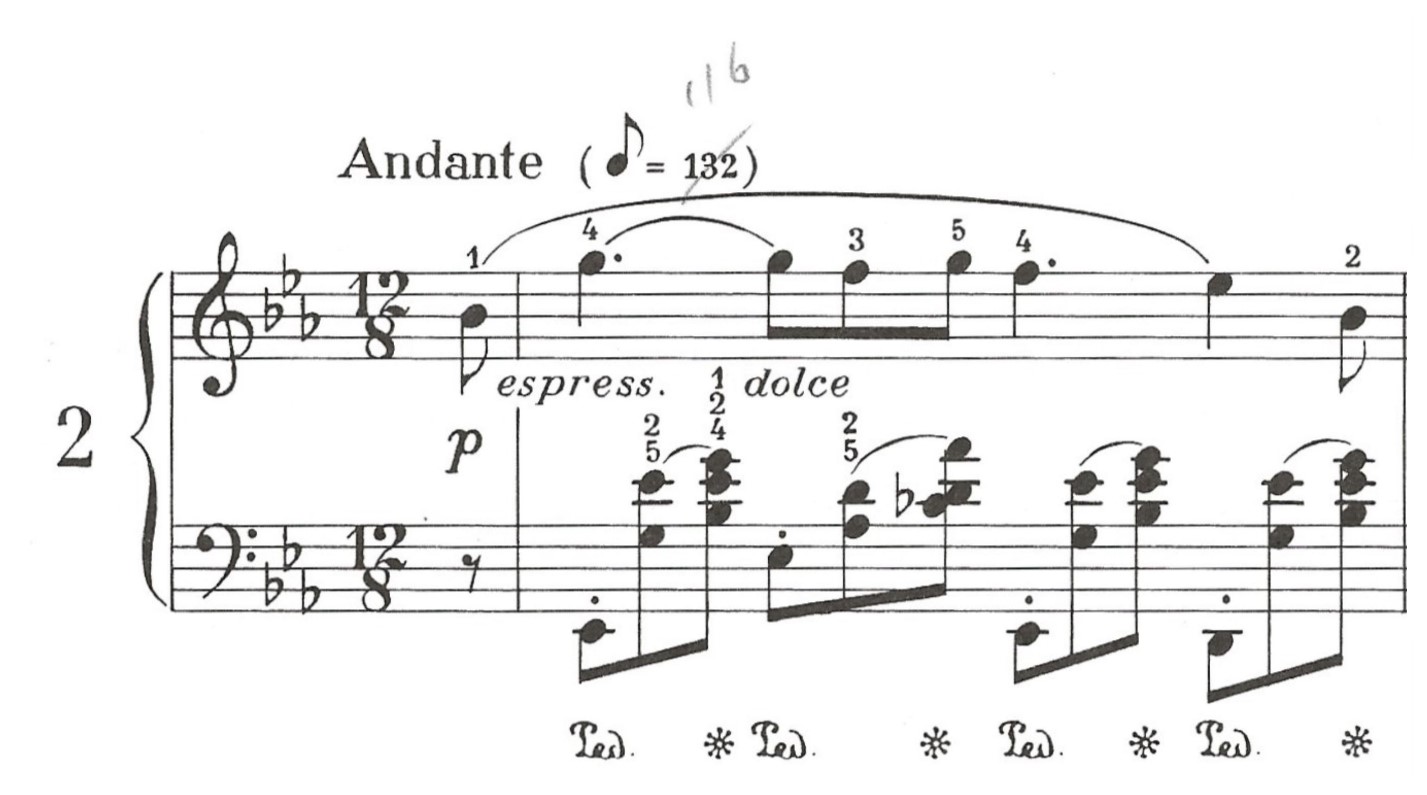

How will the listener know that Chopin Nocturne, Op. 9, No. 2 is in 12/8? What will keep them from thinking that it’s in 3/4? You need to spend a solid day mulling that over before reading the rest of this post. As part of this think-quest, consider two ideas:

- Has Chopin baked anything into this composition that would convey the written time signature to the listener over an easily-feasible, perceived-meter alternative?

- Is this matter solely in the hands of the performer?

Welcome back. My position is that there’s nothing inherent in the composition that will convey the meter in spite of what the performer does with the piece. If you feel differently, please comment. I’d love to hear from you. In the meantime though, here are some useful strategies that you, as the performer, can use to make this piece sound more like a nocturne than a waltz.

Let’s examine the opening measure. You can apply what we discuss to the rest of the piece.

First, you should play the melody as if it were in four, with triplet subdivisions, or maybe in two with sextuplet subdivisions. For expressive reasons alone, this is a must. However, I’m not sure it makes great strides toward steering clear of a waltz feeling. You should also sing the melody. I mean that both metaphorically and literally. You should actually open your mouth, and sing it as you play. Singing it brings you into an intimate understanding of what is meant by the phrase’s length. It also opens your eyes to the significant intervallic distance between the first two notes, and the beautiful length of the second note. Piano playing that isn’t informed in this way is like a vampire: lifelike in some ways, but cold and dead on the inside.

Secondly, you could suppress the accompaniment so far into the background that it barely exists. The rhythmic nature of a waltz accompaniment is critical to its character. Suppressing the accompaniment would help distance the listener from the waltz idea. Although suppression of the accompaniment is a necessary step, it is only one step in what is a more complex process. The accompaniment needs a great deal of sophistication. In the end, it can’t actually “barely exist,” but that’s its best starting point.

Thirdly, that sophistication: it takes a great deal of patience. We’re going to examine just one beat. You can extrapolate what we learn in that beat to the measure, and then to the entire piece.

- Play the first note not with your finger, but with your arm. Your arm, from the shoulder down, has to be as relaxed at it can be. Your wrist must be flexible; it acts almost like a shock absorber. The bridge of your hand (the set of knuckles nearest your palm) has to be as solid as granite while still possessing the ability to move. Your finger (whichever one you choose for this note) needs to have that same quality. If you get all of these things right, you’ll produce a full, round tone that is rich and substantial, but without aggression or edginess.

- The 6th requires an altogether different technique. You must first be in contact with the keys, and then from this position, either use your arm or a finger contraction to gently play the notes. Regardless of which method you choose, the physical action is subtle. This will produce a sound in same family as the previous note, but far, far softer.

- The chord uses yet another technique. Start once again with your fingers in contact with the keys. Then, relax everything from your wrist to your shoulder. Finally, use a slight contraction of the knuckles closest to your fingernails, as you flex your wrist and at the same time lift your forearm up and away from your body. These actions can be difficult to coordinate for someone unfamiliar with them, I’ll admit. If you get them right, you’ll produce a tone that is altogether inarticulate

Your aim in using these three techniques is to produce tones that are soft, softer, and softest. However, you’re also attempting to use color, rather than pure dynamic, for a tone that is rich, followed by one that is more neutral, and ending with one that is faded and insubstantial.

Once you’ve mastered these three techniques, you should execute the A and B techniques with the pedal, and listen to the accumulated sound. The 6th should blend with the bass note. It should not overshadow it, in fact it should leave the listener’s attention still focused on the bass note. Imagine that the 6th emerges from the bass note, blossoms from it, adds color to it, without overwhelming it. Another way to think of it: once you strike the initial tone, it immediately decays. You need to monitor this decay, and strike the second note so that it matches this decay wherever it happens to be at that moment. This can be done only with highly attentive, active listening … and lots of patient practice.

The C technique has a similar relationship with the bass note. It uses a more dramatic technique to achieve it, because the further in time one moves away from the bass note, the harder it is to achieve a proper balance, plus you’re trying to hear that bass note through the 6th that you introduced to it.

The proof of these techniques is in the ear. You have to take the time to listen and fall in love with the particular aggregation of sounds that you’re trying to create. It is difficult to achieve the perfect blend of sound in this figure, at the tempo this melody ultimately requires. Indeed, I consider this kind of demand unquestionably virtuosic.

Want a strategy for learning the 8-against-3 polyrhythm in measure 29? Click here.

Hello Jeff. After reading your excellent presentation on this celebrated Nocturne, I wonder if I may introduce you to the original variants incorporated into my performance of it on YouTube? Based on many decades of research into all original sources. With best wishes, Angela Lear

Yes, I’m very interested!

I can no longer but the suggestions given make me feel like I can.