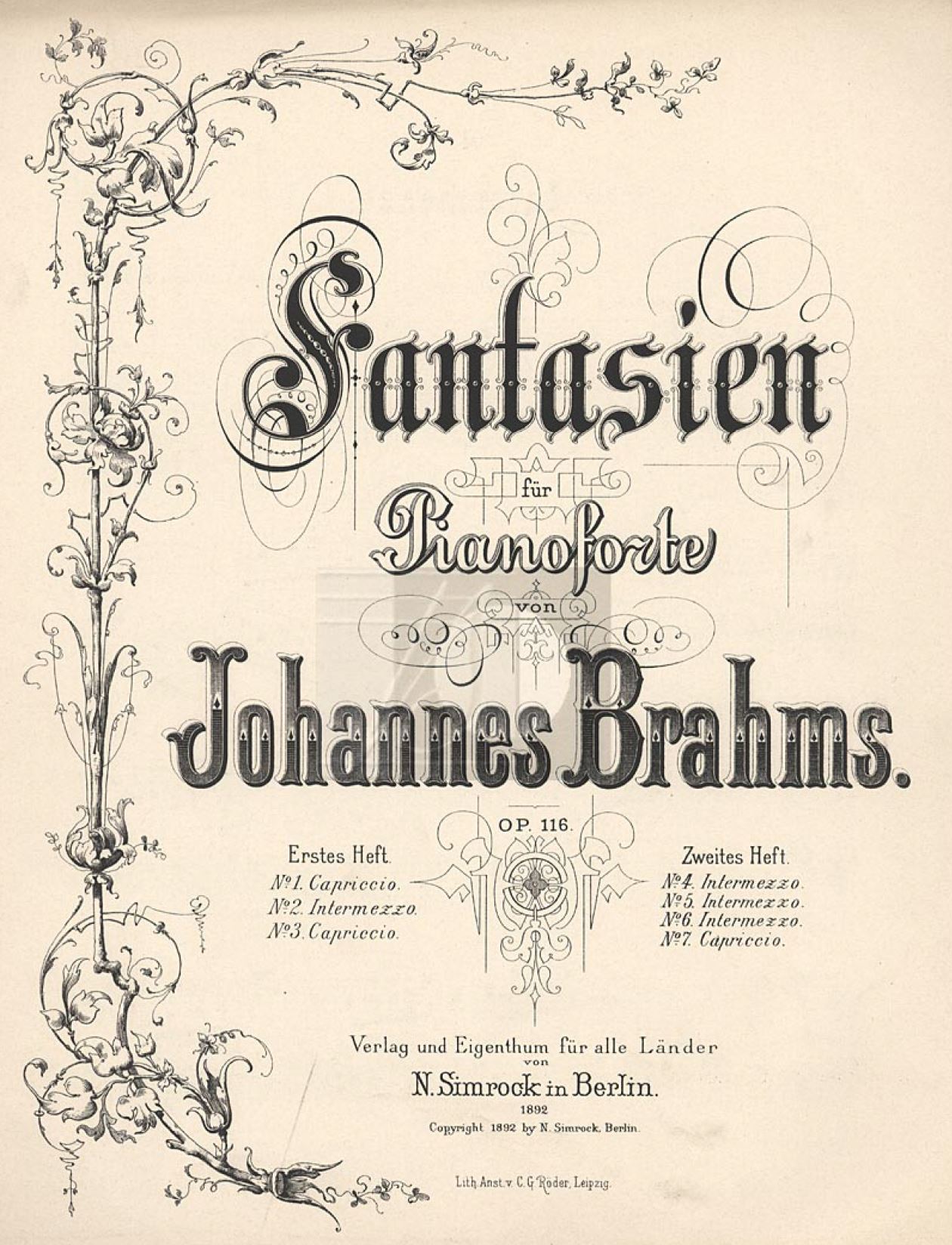

Brahms Intermezzo in E Major, from Klavierstücke, Op. 116, No. 4

Much of this intermezzo should be taken literally.

It’d be worthwhile to practice this intermezzo without the pedal at some point early on in the learning process. This would help to emphasize the literal realization of each element, what it implies, and what impact it has on the piece as a whole.

You need to make sure that you’re holding onto notes that are indicated to be held. You shouldn’t rely on your pedal to do this instead of your fingers. Doing so would decrease your options, and reduce your performance to something that could achieve only a mediocre level of sophistication.

The rests are equally important. Note that the bass clef in the first full measure ends with a quarter rest. There is room for interpretation centered around your approach to pedal. However, I question that one of the solutions would be to make the piece sound as if the C-sharp were a half-note, and the third below it dotted halves. On the other hand, a single G-sharp against a background of literal silence is too dry for my tastes. I prefer an approach in between these two extremes.

It’d be tempting to play the double-stemmed notes in m12-13 with the LH. It might also be tempting to play them in the RH, and realize the double-stems with the pedal. Taking them literally complicates the fingering, but it affects the articulation and timing in a way that is, while subtle, exquisite.

Slurs should also be taken literally. The RH at the end of m3, going through m4, should sound like two slurs, not one.

The first few measures of the bass clef exhibit interesting stemming.

The stems don’t indicate voices, but instead sometimes indicate which notes are to be held, and for how long, and other times indicate which hand plays the notes. For example, there is no bass voice that moves from E3 in the pickup measure, to E2 in the first full measure – even though the downstemming of these notes make it look like there is. Instead, the E3 has an eighth-note stem merely to connect it to the triplet, and a quarter-note stem to indicate that it should be held down and tied into the next measure. The E2’s stem is disconnected from the half notes above it – even though it functionally belongs to this group – simply to show that it’s played by the RH.

You could make an argument that the accompaniment is two-layered, with the E2 representing one of them, and all the other bass-clef notes make up the other. Even so, the E2 belongs to the accompaniment, and not to the melodic material that appears in the treble clef. For that reason, it surprises me that the first full measure of the treble clef doesn’t begin with a rest. Nonetheless, I love the uncluttered look that the absence of rests helps to create.